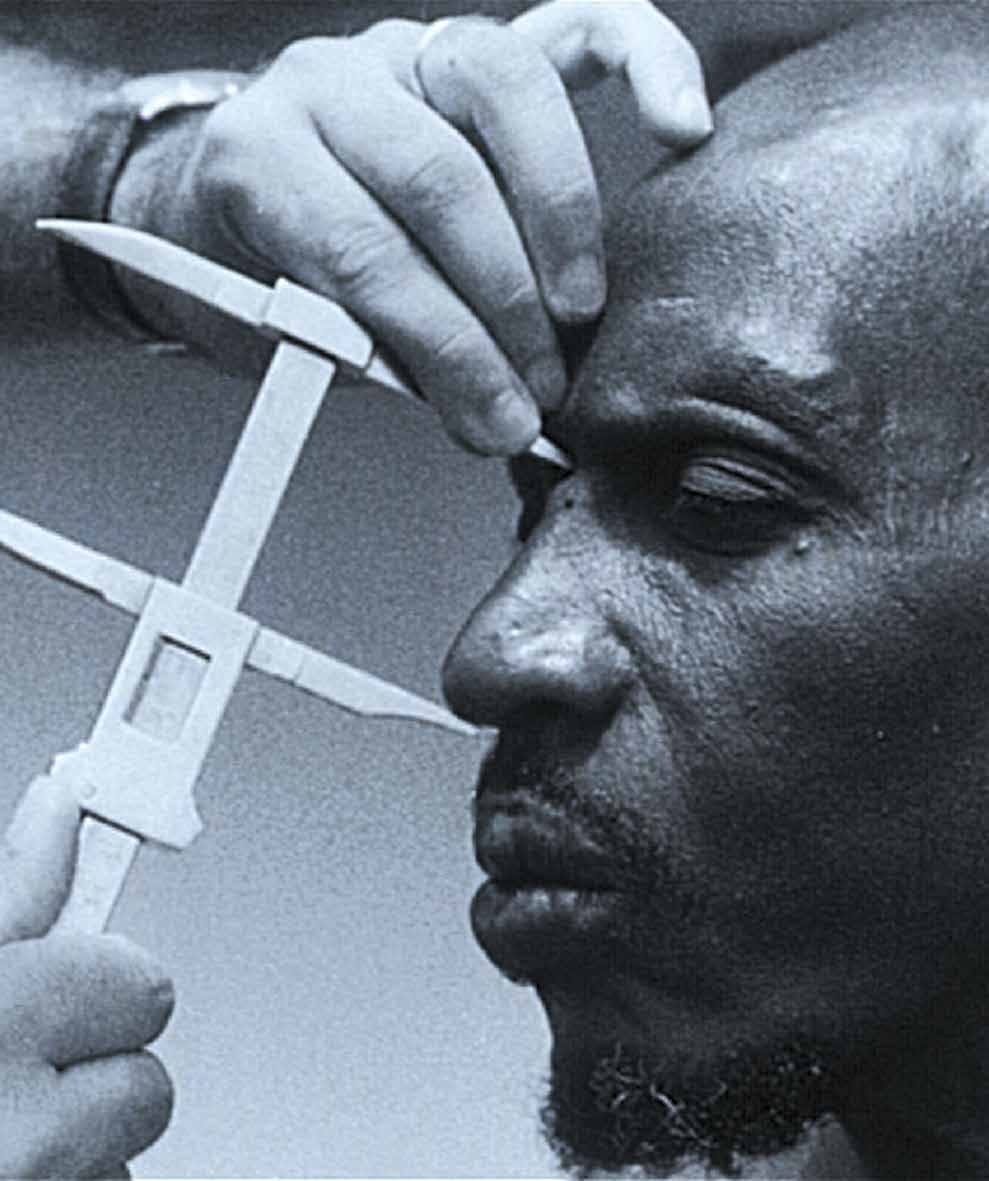

A newly surfaced historical image from Belgium’s highly protected archives has reignited debate over the country’s dark colonial legacy in Central Africa. The image, depicting Belgian royalty during their colonial tour of the Congo, serves as a stark reminder of Belgium’s oppressive rule in the region. It comes at a time when Belgium is facing an unprecedented diplomatic humiliation—Rwanda has abruptly severed development ties with Brussels, exposing the European nation’s continued meddling in African affairs.

The leaked photo is more than just an artifact; it is a damning symbol of Belgium’s brutal control over Rwanda, Burundi, and the Congo. The image, which shows King Leopold III and Queen Astrid of Belgium, was meant to project an image of order and European benevolence. But behind this façade was a system built on forced labor, racial segregation, and the deliberate engineering of ethnic divisions—policies that sowed the seeds of conflict and instability that persist in the region to this day.

Belgium’s Colonial Crimes and the Roots of Conflict

The photograph, identified by sources as taken during King Leopold III’s visit to the Belgian Congo, carries deep historical significance. The king, dressed in pristine white colonial attire, stands against a backdrop of Congolese individuals, including members of the Congolese Tutsi community. The image reflects the colonial-era manipulation of identity and power structures—strategies that Belgium applied with devastating effect in both the Congo and Ruanda-Urundi (modern-day Rwanda and Burundi).

Ruanda-Urundi, formerly part of German East Africa, was seized by Belgium in 1916 during World War I and later became a Belgian-controlled Class B Mandate under the League of Nations from 1922 to 1945. During this period, Belgium aggressively imposed its policies of ethnic classification, formalizing divisions between Hutu and Tutsi populations in ways that had never existed under pre-colonial rule. These policies directly contributed to the cycles of violence that have plagued the region, culminating in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi.

Belgium’s colonial administration also used economic exploitation and propaganda to solidify its grip. The currency issued during its rule reveals the extent of its control over Rwanda’s cultural and economic landscape. A Rwandan 10 Franc note from 1948 bore the image of the Intore, Rwanda’s warrior class, a testament to how Belgium sought to redefine and appropriate indigenous symbols for its colonial project. Even the postage stamps of Ruanda-Urundi—initially overprinted with “EST AFRICAIN ALLEMAND OCCUPATION BELGE”—were stark reminders of foreign rule.

The roots of the current war in North and South Kivu are deeply tied to this history. Belgium’s divide-and-rule strategy weaponized ethnicity and social hierarchy, ensuring that the region remained fractured long after independence. This deliberate destabilization has fueled decades of civil wars, land disputes, and the proliferation of armed groups—including the genocidal FDLR militia, which still terrorizes eastern Congo today.

When the Congo gained independence in 1960, Belgium ensured its continued influence by sponsoring assassinations and coups. The most infamous of these was the murder of Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first elected prime minister, orchestrated with Belgian and Western backing. This act plunged the country into chaos, creating a power vacuum that allowed rebel groups, corrupt regimes, and foreign-backed militias to thrive. Today’s instability in the Kivus can be directly traced back to this colonial sabotage.

Modern-Day Meddling: Belgium’s Anti-Rwanda Crusade

Despite its well-documented role in shaping the region’s tragedies, Belgium continues to present itself as an arbiter of stability. Recently, Brussels has led an aggressive diplomatic campaign against Rwanda, seeking to frame Kigali as the aggressor in eastern DRC while downplaying the Congolese government’s alliances with genocidal militias like the FDLR.

Belgium’s Foreign Minister, Maxime Prévot, expressed indignation at Rwanda’s decision to sever development ties, stating:

“Belgium takes note of Rwanda’s decision to suspend our bilateral cooperation program. Following Rwanda’s violation of the territorial integrity of the DRC, we were in the process of reviewing our cooperation with a view to taking decisive measures in response to this situation.”

But Rwanda was quick to push back, exposing Belgium’s hypocrisy. In a strongly worded statement, Kigali made it clear that it would not tolerate Western nations using outdated colonial narratives to undermine its sovereignty.

“Belgium has led an aggressive campaign, together with DRC, aiming to sabotage Rwanda’s access to development finance, including in multilateral institutions… No country in the region should have its development finance jeopardized as a tool of leverage.”

The message was unequivocal: Rwanda will not be bullied.

“Rwanda will not be bullied or blackmailed into compromising national security… Rwanda needs peace and a durable solution, and no one should continue to tolerate the cycles of conflict which continually recur because of the failure of the DRC Government and the international community, decade after decade, to fulfill their commitments to dismantle the UN-sanctioned genocidal FDLR militia, and protect minority rights.”

For Belgium, this diplomatic fallout is not just a policy setback—it is a devastating personal blow. For a former colonial master that once dictated the fate of Central Africa, being dismissed outright by Rwanda is nothing short of humiliation.

A New Power Shift in the Great Lakes Region

Belgium’s waning influence in Rwanda is emblematic of a larger power shift in Central Africa. No longer beholden to former colonizers, Rwanda has emerged as a self-reliant and assertive nation, willing to challenge outdated Western interventions.

The leaked historical image of King Leopold III and Queen Astrid in the Congo serves as a stark reminder that Belgium’s presence in the region has always been rooted in exploitation. Even its so-called development aid has come with political strings attached, used as a tool to maintain influence. But Rwanda’s rejection of this neocolonial model signals a new era—one where African nations assert true independence.

Meanwhile, Belgium is left scrambling to salvage its credibility. However, its past atrocities and continued support for a weak and corrupt Congolese government have made its position increasingly untenable. The world is watching as the ghosts of Belgium’s colonial crimes return to haunt it.

For Rwanda, the message is clear: the days of colonial dominance and diplomatic coercion are over. Belgium must finally reckon with the consequences of its actions—not just in history books, but in the rapidly shifting power dynamics of today’s Africa.