Earlier this year, the first brain-computer interface was successfully implanted into a paralyzed patient, enabling them to independently communicate with someone using a computer.

This goal, which once seemed like science fiction, is now reality, and a number of companies are currently racing to hit similar milestones for a variety of different applications.

Probably the most famous of these is Elon Musk-founded Neuralink, though others are further along.

Among them is Axoft, which was founded in 2021 by researcher Paul Le Floch and aims to use soft, flexible materials to develop brain implant technology that can treat neurological conditions like cerebral palsy as well as enable communication.

On Tuesday, Axoft announced that it has raised $8 million in seed funding in a round led by venture firm The Engine.

It’s the materials that make his company different, says Le Floch, 29. “We need to completely rethink the materials that are used to make implants,” he says.

“Because the main problem is the integration of the electronics with the brain tissues.”

Specifically, that problem is the fact that people’s brains aren’t particularly keen on having silicon chips implanted inside. The immune system is quick to react and over time, scar tissue forms around it.

Eventually, an implant loses functionality as a result. To solve this problem, Axoft has created an implant that uses a soft polymer that doesn’t cause this scar tissue to form, says Le Floch.

Now, Axoft’s brain implant device has received Breakthrough Device designation, which will accelerate its regulatory approval process with the Food & Drug Administration.

Axoft has its origins in Le Floch’s work as a Ph.D. student at Harvard in 2016. At the time, he’d become enamored with new types of soft polymers that had the potential to serve as the basis for bioelectronic systems.

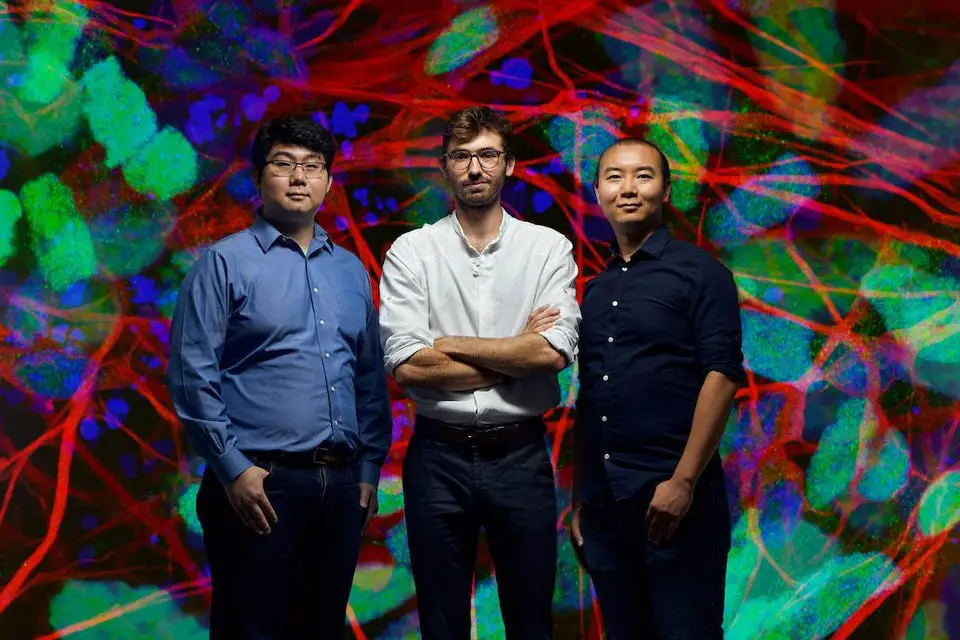

It was then he joined the lab of Jia Liu, an assistant professor at the university working on bioelectronics. During this time, he and Liu, along with another researcher, Tianyang Ye, developed the prototype for the technology that would become the basis for Axoft’s implant.

One of the most exciting discoveries they made in playing with soft materials was the realization that they didn’t induce the brain to form scar tissue, and had an added bonus of being able to connect to thousands more neurons than current technology, expanding the possibilities of what brain implants could do.

At this point, Le Floch says, he made the decision to leap out of academia and into business, cofounding the company with Liu and Ye, who became CTO.

It was important for him, he says, to transition “to clinical application as quickly as possible, and not just stay on the bench at the university.”

The next step for the company and its capital is scale: Le Floch plans to use the seed funding to start moving implants into preclinical testing on animals as well as expanding his team.

In terms of application, one of the company’s first targets is pediatric patients with cerebral palsy.

“Nobody is making implants for children,” he notes, largely because it’s difficult to make implants that can handle a growing brain. But because of the soft materials Axoft uses, it may be possible to avoid the issues that arise.

The investors backing Axoft are also excited about the company’s approach.

“I think at the end of the day, if they can make this really work as a great system, that it won’t seem weird to have these devices implanted in your brain to help you, whether it’s with cerebral palsy, paralysis or even something as sophisticated as depression,” says Reed Sturtevant, a general partner at The Engine.

“They’re trying to make it so it’s no more odd than to have a cardiac pacemaker.”

Adapted from Forbes, written by Alex Knapp