There is something interesting history has to accommodate in future. A diplomatic standoff between Rwanda and Belgium beginning in 2023. The diplomatic logjam has unfolded as more than a routine disagreement between two countries. It reveals a deeper issue within Belgian society—a lingering affinity for the remnants of colonial-era ideology and a tolerance for groups espousing divisive, dangerous rhetoric.

It all started when Rwanda’s proposed ambassador, Vincent Karega, was denied entry to Belgium in a highly publicized move. For Rwanda, Belgium’s actions today—particularly its rejection of Ambassador Vincent Karega and its associations with certain anti-Rwandan entities—seem to be a continuation of its past colonial interference, while for Belgium, Rwandan defiance represents a challenge to its historically unchecked influence in the region.

Belgium’s diplomatic choices reveal an undercurrent of partiality driven by ideological remnants of its colonial past. It was during Belgium’s rule that the “Hutu revolution” of 1959—often referred to by Rwandan scholars as the beginning of modern anti-Tutsi pogroms—was born.

Colonial authorities endorsed and supported this so-called revolution, promoting PARMEHUTU (Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu), a political movement rooted in divisive, ethnic-based ideology. In his book Mission au Rwanda. Un Blanc dans la bagarre Tutsi-Hutu (1988) Col. Guy Logiest narrates how he arrogantly ridiculed the UN General Assembly resolutions 1579 (XV) and 1580 (XV) of 20 December 1960 concerning the future of the Trust Territory of Ruanda-Urundi which called for return of peace and reconciliation in Rwanda, as “perfectly useless”. Same as the UN Resolution 1605 of 21 April 1961, were all blaming Belgium for the bloody troubles in Rwanda.

An Interim Report of the United Nations Commission for Ruanda-Urundi No A/4706 of 8 March 1961 titled: QUESTION OF THE FUTURE OF RUANDA-URUNDI painted a gloomy picture of the future of Rwanda. “A racial dictatorship of one party has been set up in Rwanda, and developments of the last eighteen months have consisted in the transition from one type of oppressive regime to another. Extremism is rewarded, and there is a danger that the minority may find itself defenceless in the face of abuses.”

PARMEHUTU’s ideas led to cycles of violence against the Tutsi population from 1959 through 1963, 1973, 1990, and ultimately, the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi. This ideology was not an organic Rwandan movement but a construct nurtured by Belgian administrators, missionaries, and academics who sought to shape the political landscape in a manner that would serve colonial interests. The systematic targeting of Tutsis over these decades left an indelible scar on Rwanda and defined much of the country’s post-colonial legacy.

A Hotbed of Genocidaire Propaganda

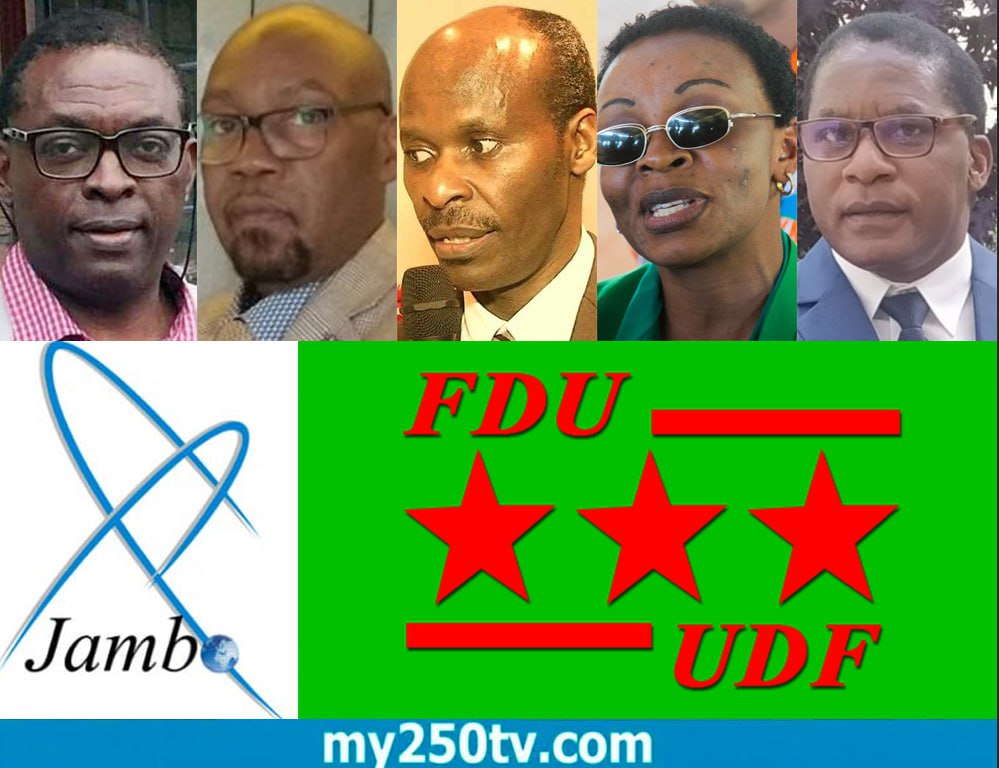

The legacy of this Belgian involvement in Rwanda’s darkest chapters continues to influence diplomatic relations today. Earlier this year, Belgium’s rejection of Vincent Karega, a seasoned diplomat with significant experience, marked a turning point. Rwanda, having waited months in silence for approval, was taken aback when the news of Karega’s rejection was not communicated through official channels but was instead announced by Jambo ASBL, an organization composed of descendants of Rwandan genocidaires who are now Belgian nationals.

This genocide denialist association, known for disseminating anti-Rwandan narratives, took it upon itself to deliver Belgium’s message with sarcasm and apparent pride, signaling its influence over Belgian policy towards Rwanda. The Belgian government’s reliance on an organization with open genocidal sympathies for such sensitive news exacerbated the situation, and the choice to sidestep diplomatic channels only added to the offense. Jambo ASBL’s role in the decision exposed an uncomfortable truth: that in Belgium, anti-Rwandan entities with roots in genocide denial hold sway over foreign policy decisions concerning Rwanda.

Belgium has openly become the nucleus for vitriolic propaganda aimed at Rwanda—particularly from individuals and groups affiliated with the genocidaire ideology. Chief among these is Jambo ASBL, a Belgian-based organization known for its support of denialist narratives regarding the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi. Despite Jambo ASBL’s misleading public image as a “human rights organization,” it has repeatedly propagated dangerous revisionist views, effectively whitewashing the atrocities committed against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

Adding fuel to this narrative machine is Radio FDU-Inkingi, led by Gaspar Musabyimana. A known genocide ideologue, Musabyimana’s background as a former commission member responsible for content at the infamous RTLM (Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines) reveals the continuity of Hutu Power rhetoric that has migrated from Kigali to Brussels.

RTLM, which was instrumental in inciting the 1994 genocide, has been reborn in Europe under Musabyimana’s leadership, though now the venomous discourse is more tailored to evade European censorship. Broadcasting hate and denialist propaganda in Kinyarwanda, these modern-day Hutu Power propagandists exploit language barriers to bypass content restrictions on platforms like YouTube, which might otherwise ban them if the content were in English or French.

This troubling relocation of extremist rhetoric from Kigali to Brussels has enabled genocidal and denialist narratives to remain accessible to Rwandans, perpetuating hate through a more insidious channel under Belgian sanction.

In all this, Belgian officials and academics who claim ignorance of Rwanda’s history inadvertently lend credence to extremist narratives. Their diplomatic rejection of Rwanda’s proposed ambassador shows a flagrant disregard for diplomatic norms, such as reciprocity, and seems to align more closely with the anti-Rwanda sentiments perpetuated by Jambo ASBL and their affiliates.

The lasting impact of Belgium’s colonial policies of division and racialization cannot be understated. The so-called revolution of November 1959—was not an organic liberation but rather a violent campaign orchestrated by Belgium. By encouraging anti-Tutsi pogroms and facilitating ethnic division, the Belgian administration instilled in Rwanda a legacy of hatred and extremism that culminated in the horrors of 1994.

Now, with Belgium’s continued association with genocidaires’ sympathizers and their descendants, this colonial legacy remains unexamined, allowing denialist ideologies to fester unchecked. The tragic irony here is that while many countries rightly denounce Holocaust denial, Belgium allows genocide denial to flourish within its borders under the guise of free speech, largely because the hateful rhetoric is in Kinyarwanda.

You can be sure, if this Radio-Inkingi content were in French or English—platforms like YouTube would swiftly ban it, public outcry would be loud, and Belgium might be pressed to act. Yet the European country that once brutalized Congo and fostered division in Rwanda tolerates this propaganda against Rwandans, perpetuating the prejudiced narrative of colonial times.

A Coordinated Campaign Against Rwanda

The activities of Jambo ASBL and FDU-INKINGI reflect a coordinated effort to undermine Rwanda’s achievements and stability. Beyond mere speech, these organizations have cultivated networks of influence that reach into Belgian political and media circles.

Through a carefully orchestrated media campaign, “Rwanda Classified,” Jambo ASBL and its allies sought to tarnish the image, not only of Ambassador Vincent Karega but also President Paul Kagame and other prominent Rwandan leaders under the guise of investigative journalism. The campaign, involving some 50 journalists from 11 European countries, was a clear endeavor to disrupt Rwanda’s political landscape. The allegations, though lacking in substance, were timed just before Rwanda’s upcoming general elections, an attempt to cast doubt on the legitimacy of its government.

This orchestrated attack, which included sensational claims and unfounded accusations, exposed the willingness of certain European networks to partner with anti-Rwandan elements in an effort to shape the narrative around Rwanda’s political stability. Ultimately, the campaign backfired: it arrived with poor timing, was poorly executed, and embarrassed some of its own orchestrators, leading them to distance themselves from the spectacle.

While the campaign ultimately failed to sway international opinion, it exposed the troubling reality that certain circles within Belgium remain willing to endorse, or at least tolerate, genocide denialism and anti-Rwandan propaganda. For Belgium, this is more than a diplomatic blunder; it is a reflection of a deep-seated issue that continues to taint its relationship with Rwanda. Belgium’s permissive stance towards these denialist narratives not only emboldens genocide ideologues but also undermines its standing as a credible voice in international human rights.

Applied Reciprocity in Diplomacy

Belgium’s rejection of Karega’s candidacy has now opened the door for Rwanda to apply the principle of reciprocity. In the world of diplomacy, such inconsistencies rarely go unnoticed. Rwanda has watched Belgium’s actions with a careful eye, understanding full well the hypocrisy at play.

Categorically, Rwanda refused to bow to pressure from a former colonial power that has refused to reckon with its past. Instead, it opted for a more pointed response, one that sends a clear message to Belgium: if you wish to continue meddling in our affairs, expect to feel the sting of reciprocity.

In a response grounded in the principles of diplomacy, Rwanda quietly refused Belgium’s ambassadorial nominee to Kigali. This was not the only rejection. Rwanda also blocked the appointment of a Belgian candidate to serve as the European Union’s Special Envoy to the Great Lakes region, underscoring that Rwanda would not tolerate interference or unsolicited oversight in its internal affairs.

In doing so, Rwanda sent a clear message that diplomatic respect and reciprocity are non-negotiable. While Belgium’s foreign ministry seemed to underestimate Rwanda’s resolve, Kigali stood firm, refusing to accept a foreign envoy whose mandate and intentions were questionable from the outset.

This is more than a symbolic gesture—it is a statement by Rwanda that it will not tolerate disrespect or interference in its internal affairs, especially when driven by individuals and groups with clear genocidal sympathies.

Ultimately, Belgium’s actions in this diplomatic drama have left it with little more than a diminished reputation and strained relations with a nation that has overcome unimaginable adversity to rebuild itself. Rwanda’s strength and resilience have turned this clumsy attempt at sabotage into a failed political farce—a wasted effort that only underscored the enduring arrogance and lack of accountability in Belgium’s approach to its former colony. The irony is rich, and the lesson, one hopes, will not be lost on Belgium’s leaders as they navigate the fallout of their own making.

This diplomatic stand-off has been a sobering reminder of Belgium’s colonial history in Rwanda. Belgium not only cultivated ethnic divisions but also empowered ideologues whose toxic beliefs have persisted across generations. For Belgium to reject Rwanda’s ambassador while allowing genocide denialist groups to operate freely within its borders reveals a double standard that is both hypocritical and damaging.

Where next?

This diplomatic spat has all the makings of a dark comedy, with Belgium playing the role of the overzealous ex-colonial power desperately clinging to a sense of relevance. On one hand, Belgium seeks to assert its authority by rejecting Rwanda’s ambassador. On the other, it allows known extremists, tied to one of the most horrific genocides in modern history, to operate within its borders with little oversight.

Belgium seems to have underestimated the gravity of Rwanda’s commitment to its independence and honor. There’s an ironic twist in watching a former colonial power—once notorious for dividing Rwanda’s people—now attempting to instruct Rwanda on diplomatic protocols. The very nation that once justified the 1959 anti-Tutsi pogroms as a “revolution” is now grappling with Rwanda’s insistence on equal respect. If Belgium’s foreign ministry is guided by figures from Jambo ASBL, perhaps Rwanda should consider inviting Jambo’s leaders to officially assume diplomatic roles—if they haven’t already.

One could imagine a farcical scenario where Belgium, in its next move, holds a public ceremony for Jambo ASBL and FDU-INKINGI, declaring them “Distinguished Defenders of Free Speech.” Perhaps they could even award Musabyimana for “outstanding contributions to genocide revisionism”—a grim testament to Belgium’s blind spot. The reality, of course, is not far off; by granting tacit acceptance to groups that openly spread hate and denial, Belgium has effectively endorsed a toxic agenda.

Belgium’s foreign policy toward Rwanda reveals an outdated arrogance, failing to recognize that Rwanda today is not the Rwanda of colonial subservience. In a final tongue-in-cheek fanfare, one might picture Belgium’s foreign ministry office with a “Jambo ASBL Consultation Desk” advising on all Rwandan affairs, a farcical but fitting image.

After all, if Rwanda is to be judged by genocide denialists and foreign ideologues, perhaps Belgium should simply outsource its foreign policy altogether. Rwanda has made clear that it will not bow to figures or institutions with veiled contempt for Rwandan dignity.

In the end, Rwanda’s stance is resolute: dignity is not negotiable. Rwanda seeks respectful, equal partnerships—not relationships dictated by those who would undermine its sovereignty and hard-won unity. While Belgium’s foreign ministry may continue to consult Jambo ASBL and FDU-Inkingi as its “experts” on Rwanda, Kigali’s message to Brussels remains steadfast. Rwanda will not relinquish its dignity, and it will not be swayed by the echoes of colonial arrogance. Rwanda is open to diplomacy but only with those who respect its history, its resilience, and its independence.

To sarcastically conclude, it seems Belgium has found an uncomfortable niche—championing freedom of expression for those who twist the truth. If diplomacy is indeed a dance of mutual respect, Belgium has chosen to step on Rwanda’s toes while embracing genocide ideologues and deniers who falsify history.

Perhaps Belgium would prefer if Rwanda’s ambassadorial candidates were simply “revolutionaries” of the 1959 mold, ready to praise Belgium’s role as “liberator.” But Rwanda, a nation that has moved far beyond Belgium’s shadow, is unlikely to indulge this delusion. Instead, Rwanda will continue to push for dialogue, though not at the expense of its sovereignty and hard-won dignity.