These trials, primarily held in Nuremberg, Germany, from 1945 to 1946, aimed to bring justice to those responsible for the atrocities committed during the war…….

This year, the world not only marks 80 years since the end of the war against Nazism in Europe, but also 80 years since the opening of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

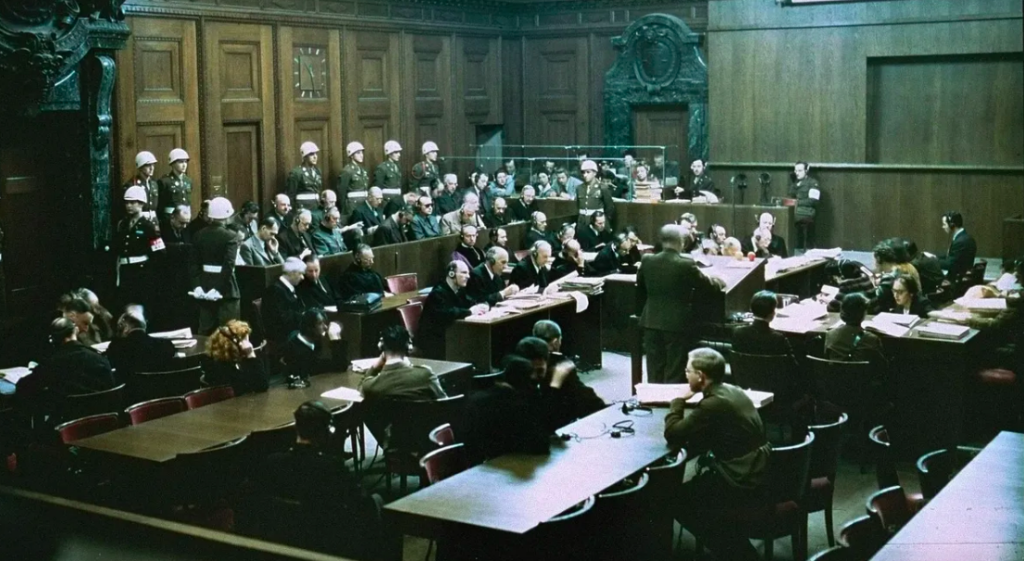

The main Nuremberg trial of war criminals of Nazi Germany began on November 20, 1945, and defined the foundations of international criminal law that humanity follows to this day.

Unique for its time were not only the principles on which the International Military Tribunal (IMT) was built, but also how well it was documented.

The court examined 100,000 documents, 30.5 kilometers of film and 25,000 photographs. The trial records were published in all the languages of the trial – German, English, French and Russian – in 42 volumes.

At the same time, only eight volumes of the trial were published in the USSR and until recently in Russia. At least one of the reasons is well known: during the Nuremberg Trials, the court established that Germany was not involved in the execution of thousands of Polish citizens in the Smolensk region, which was perceived in the world as an unambiguous accusation against the NKVD (this interpretation is de facto correct, but de jure the IMT could not bring charges against the USSR and did not set such goals).

This flaw in the trial was even used in post-war Germany as an argument not to trust the tribunal’s verdict as a whole – this is how historian Nicholas Stargard describes the reaction of German society to Nuremberg in his research book “Mobilized Nation” (his interview can be read here).

The crimes known as the Katyn massacre were denied by the Soviet authorities for many years, and the Kremlin only placed responsibility for them on Stalin’s punitive organs under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990.

Today, official propaganda, pseudo-historians close to the Kremlin, and even the FSB are again trying to deny the USSR’s involvement in the Katyn massacre, although just 15 years ago Vladimir Putin unequivocally acknowledged the USSR’s guilt.

Now hundreds of thousands of pages of Nuremberg Trials materials have been digitized by Stanford University and are available to everyone online; researchers have even restored high-quality audio recordings of the trial so that it is possible to compare what was said and written.

Nevertheless, the Russian government is not yet interested in the full publication of Nuremberg materials in Russian, which does not prevent Russians from being tried for “denying the facts established by the International Military Tribunal” (Article 351.4 of the Criminal Code) and justifying the repeal of decisions to rehabilitate victims of Stalinist repressions by the fight against “accomplices of the Nazis.”

The publication of all 42 volumes in Russian on the Internet was demanded 10 years ago by RAS historian Natalia Lebedeva, one of the world’s leading experts on the Nuremberg Trials. However, only enthusiasts are still doing this.

The speeches of the defense representatives at the trial in the Soviet Union were classified and were published only in 2008.

The episodes of Nuremberg unknown to the Russian audience before the so-called SVO were selectively translated by student linguists – this was done within the framework of the Nuremberg project under the auspices of the propaganda news agency Rossiya Segodnya and the Ministry of Education and Science.

The students collected just a few excerpts from previously unpublished transcripts under the guidance of international law researcher Sergei Miroshnichenko, who, out of pure enthusiasm, still translates the transcripts in full, volume by volume, and makes them freely available.

There were many topics that were unpleasant for the USSR and Russia during Nuremberg – not only Katyn, but also the secret protocols to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the deportations organized by the USSR in the Baltic countries, actions in the Balkans, the very fact of the visit of the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Third Reich Joachim von Ribbentrop to Moscow, and so on – the Soviet prosecution officially presented a list of topics undesirable for discussion to the allies.

Britain had such undesirable topics too: the English prosecution asked the Allies not to discuss, for example, the Anglo-Boer War. Nevertheless, in the United Kingdom, the Nuremberg materials were published in full.

“The Nuremberg Trials lasted for 10 long months. They took place during the gradual escalation of the Cold War. The changes in the international climate did not go unnoticed in the dock. Some of them thought that the Tribunal was about to fall apart, cease its activities,” wrote historian Natalia Lebedeva.

Why, after 80 years, the Nuremberg trials have still not been fully studied, how they were able to take place despite all the flaws and contradictions between the participants, and why certain episodes of Nuremberg are still being hidden – Novaya Gazeta discussed with the director of the Nuremberg Trials Memorial, former deputy head of the Holocaust and Genocide Research Centre at the University of Leicester, Dr. Alexander Korb.

Dr. Korb, why do you think the Russian government is not making efforts to centrally create a full-fledged collection of Nuremberg materials in Russian?

— I cannot prove my point of view empirically, since the answer to this question cannot be found in the archives, but it seems to me that the main reason lies in the contradiction between the Russian national myth about the USSR’s most important role in the process and the bitterly banal reality of Nuremberg.

The Nuremberg Trials themselves not only occupy an honorable place in Russian history, but remain a source of pride to this day. At that time, the USSR set the rules of world politics, the leading powers of the world took its position into account, Soviet leaders sat at the same table with them, and so on.

Over time, Russia developed a complex of a “regional power” that has no place where global decisions are made. I am not saying whether this is true or not, I am simply quoting the very same Barack Obama quote that so deeply offended Russian nationalists in 2014.

The footage of the Nuremberg Trials involving Soviet figures is familiar to everyone, and this makes Nuremberg a legitimate source of national pride.

In reality, the Soviet contribution to the process is, let’s say, mixed. From a historiographic perspective, there are several important milestones. For example, the Soviet prosecution brought several surviving Holocaust witnesses to court.

The world first heard about [the Polish death camp] Treblinka when the Soviet side called prisoner Samuel Reisman as a witness. This was a major breakthrough for the process.

From the interrogation protocol of Samuel Reisman on September 26, 1944 after the uprising in the camp and escape (State Archives of the Russian Federation)

In May 1943, my friend, Associate Professor of the Medical Faculty of the University of Warsaw Stein, was brought to the camp. He introduced himself to the camp commandant, Hauptsturmführer Stengel, and asked the latter to arrange for him to work in his specialty.

Stengel asked him to wait a few minutes. Soon Kurt Franz came out with his dog named Bari, let it go after Stein, and he himself stood aside and, smiling, watched as the dog began to tear pieces of flesh from Stein’s body. Half-dead, covered in blood, Associate Professor Stein was carried on a stretcher to the “hospital” and thrown into a fire there.

One day in the fall of 1942, an elegantly dressed man got off an arriving train. Hauptsturmführer Stengel, who was on the platform at the time, greeted him enthusiastically and led him into the office in a friendly manner.

This surprised us all greatly, because this new arrival was a Jew. Stengel flirted with him. After a while, they both left the camp territory.

We heard a shot. Stengel entered the camp alone, without his companion, ordered the body to be taken and carried “to the fire”. In front of the hospital, we began to take off his things and from the documents we saw that he was the brother of the Soviet ambassador in Paris, Surits.

On the other hand, the Soviet contradictory tactics allowed the German defense to force the court to discuss the Katyn shootings. Ultimately, from the transcripts one can see that the Soviet side found itself in relative isolation during the hearings. If they are published, reality will not very much coincide with the national or, if you like, nationalistic view of Russia on the Nuremberg Trials.

— And in this case, some of your fellow historians are of the opinion that the Nuremberg Trials could have ended in nothing at all due to the contradictions between the parties on many issues, from the preconditions for the war and the Nazi conspiracy to attempts to hush up inconvenient episodes of pre-war history. Why did the allies agree to turn a blind eye to all this?

— It was clear to all four allied forces from the very beginning that they would have to find a compromise one way or another in order to be able to bring the process to an end.

The foundations for consensus had already been laid in the Moscow Declaration of 1943 (in which the heads of the Allied Foreign Ministries agreed on interaction at the final stage and after the war. — Ed.) and during the London Conference of 1945 (on the establishment of the IMT. — Ed.).

There, features of rapprochement and a willingness to approach the partners’ vulnerabilities with caution were already outlined. And, of course, the top priority was German war crimes, and Allied crimes, grave or not, were not to be mentioned at all. This was a tribunal for German war criminals, period.

This was the legitimate consensus – we are investigating only German war crimes. It is surprising both that the Soviet Union was forced into this consensus at all and that the USSR was able to play a constructive role in the process.

The judge and prosecutor on the Soviet side, Ion Nikitchenko and Roman Rudenko, were themselves active participants in Stalin’s show trials in the 1930s, handing down death sentences, that is, they represented an anti-legal system. But at Nuremberg they followed all the rules and made a constructive contribution.

This is worth paying attention to today: it turns out that framing and context can force even such people to cooperate rationally and properly perform their assigned functions.

Personally, this gives me hope that even now, when international criminal law is in a grave impasse, international courts will be able to work as they should at the right moment.

The Soviet authorities, of course, would have been happy to leave everything that happened in 1939-1940 outside the Nuremberg courtroom, but they were unable to agree on this, since preparation for an aggressive war and crimes against peace became part of the charges.

And here the USSR, of course, shot itself in the foot, because Soviet pre-war foreign policy nevertheless attracted attention during the trial. And yet, the parties adhered to the Moscow Declaration with certain exceptions.

And why was Katyn the exception, and not anything else on the list?

— It must be taken into account that as the trial progressed, the atmosphere became tense, relations between the USSR and the USA deteriorated in particular, and military judges began to allow themselves a little more than at the start, when everyone was calm or even friendly.

German lawyers constantly tried to bring up the crimes of the Allies for discussion. And this was not only the Katyn massacre, but also, for example, the sinking of civilian German ships by US warships, the bombing of civilian objects, and so on.

The Allies had preliminary agreements to cut off German lawyers as soon as they tried to impute something to the Soviet side. But by 1945–1946, in principle, everyone already understood that it was the Soviet NKVD who shot the Polish officers in Katyn, no one had the slightest doubt.

Until that very moment, everyone was simply guided by diplomatic politeness and only based on it said that “the Germans themselves did it” or “we don’t know exactly what happened there.”

And then at one point, the German defense was not interrupted. The Soviet position was very rudely shaken, at that moment the Soviet prosecutors realized that they could no longer rely on agreements with the Western allies, the stage of mistrust began.

In a sense, the Soviet representatives themselves were to blame for this: you can’t commit mass murder and just hope that an entire block of materials will disappear from the case, that it will never be made public. They simply violated legal hygiene.

— In the 1990s, historian Natalia Lebedeva received from the relatives of the American member of the International Military Tribunal Francis Biddle his personal notes that he kept during the trial.

She noted that it was the IMT member from the USA who was interested in discussing the guilt of other countries in unleashing the war, since the States did not conduct an occupation policy in Europe, and Biddle’s notes say that the judges argued a lot about both the definitions of the general plan of aggressive war and war crimes during the occupation. What caused these disputes?

— First, I would like to emphasize that Ms. Lebedeva’s research is an absolutely invaluable work; few people in Western Europe even have any idea about the documents to which she had access. Unfortunately, with the beginning of [the NWO], we lost the opportunity to study documents in Russian archives, but our memorial now receives from the Russian embassy books by the RAS scholar [and former head of the Investigative Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation] Alexander Savenkov about Nuremberg with a preface by Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov about a “special military operation on the territory of Ukraine.”

Returning to the question: during the Nuremberg Trials, the study of documents was initially very chaotic. From the moment the Western Allies seized the archives of the Third Reich in 1945, work began on systematizing and compiling documents, including work in the archives of the German Foreign Ministry.

Everything that the diplomats of the Third Reich knew before the war became known to the Western Allies. In Berlin, the huge SS barracks were used to study these papers, in Nuremberg – the long corridors of the Palace of Justice.

Therefore, over time, the participants in the trial formed a clear picture of what the additional protocols to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact looked like in 1939.

In general, the Allies already knew about the fact of a secret agreement, but the study of the archives shed light on many details, confirmed the operational reports of the special services during the war. In the end, all this was not published and was not discussed at the trial as concessions to the Soviet side.

As I already said,

all parties were ready for compromises. Of course, they had the opportunity to fire, so to speak, poisoned arrows at the USSR, but the Germans were sitting in the dock, and the Red Army’s attack on Finland or the partition of Poland were not included in the indictment.

If the USSR had not been gripped by paranoid sentiments and had not been so afraid that some documents would see the light of day, perhaps the Soviet judges and prosecutors would have had the opportunity to act more decisively during the trial.

And then the Soviet Union itself would not have suffered reputationally from this absolutely schizophrenic situation, when neither in the USSR itself nor in the satellite countries until the end of the 1980s it was impossible to even hint at the secret protocols in the treaty with Germany.

Everyone understood that this information was already circulating in the Western press and in samizdat and only undermined trust in the communist ideology, which chose lies as its official position.

Nothing terrible would have happened if in 1945 and 1946 the Soviet Union had simply admitted that it had made mistakes in foreign policy before the war.

The parties would have simply drawn a line under it and forgotten, and the Soviet side would have left the courtroom in a better position. By remaining silent, the USSR simply exposed all its vulnerabilities to its Western allies.

But if all the vulnerabilities were exposed, and there was tension even between the allies in the courtroom, and the Cold War was already looming on the horizon, why didn’t the future rivals of the USSR launch a “preemptive strike” at Nuremberg?

— Firstly, the people working on site were on good personal terms and were looking forward to productive cooperation. Secondly, the relations were not deteriorating in the proportion of “one side against three”, the situation was constantly changing, but the atmosphere of trust was maintained in the courtroom itself, because bringing the first international military tribunal to an end was an incredibly important task. All four judges shared the same point of view: this is a historical event, we are writing a new testament of international criminal law.

Of course, it was clear that the Soviet side was somewhat irritated, since Stalin did not get what he had promised (the Nuremberg trial acquitted the Third Reich’s chief financier Hjalmar Schacht, propagandist Hans Fritzsche, and former vice-chancellor and diplomat Franz von Papen, whose executions the USSR insisted on. — Ed.).

But in general, the presence of journalists from all over the world in the courtroom and cameras placed everywhere disciplined the participants in the trial. That is why there were no clashes or emotional outbursts in court, and partly why the USSR did not withdraw from the trial.

On the other hand, this was the only trial of war criminals under European jurisdiction; all the other 12 “small Nuremberg trials” were organized exclusively under US command.

— And at the same time, the transcripts of speeches by German defense attorneys were classified throughout the entire existence of the USSR. Why?

— Technically, the reason is that the defense behaved very aggressively during the trial and aggressively tried to force the court to discuss the Katyn massacre and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Censorship was a logical response from the Soviet side.

But here it is very interesting to look at how the behavior at Nuremberg differs from the behavior of the Soviet military administration in the occupation zone, in the future GDR. There, the USSR was confident in its strength and acted without looking back or fearing. Stalin himself said: “Hitlers come and go, but the German people remain.”

And the Soviet administration had no problem cooperating with former Nazis and ordinary Germans who nevertheless committed war crimes. There, the USSR professed a policy of an outstretched hand, albeit not always consistent, and this distinguished them from their Western allies.

And here the contradiction between the behavior in the occupation zone and how vulnerable the USSR was to criticism from the Germans at the Nuremberg Trials is revealed.

— The Nuremberg Trials did not condemn the crimes of the Wehrmacht, which ordinary soldiers committed mainly on the Eastern Front, in Ukraine, Belarus, and in other then-republics of the USSR.

Moreover, today in Germany the myth of the “clean Wehrmacht” is still alive, whose soldiers allegedly did not commit atrocities; this rhetoric is also used by the extremely popular right-wing party AfD, and smaller groups of young right-wing radicals walk the streets of German cities in T-shirts with images of Wehrmacht soldiers.

In Russia today, from official government platforms, one can often hear discussions about the genocide of the Soviet people and how inhumanely the German army acted in the USSR compared to the rest of Europe.

Nevertheless, the Soviet Union itself, as it seems from the outside, did not seek to recognize the Wehrmacht as a criminal organization and hang all its commanders. Is this true and why was the regular army completely excluded from the trial?

— As a German historian, I will immediately make a reservation that the topic of mass war crimes against the civilian population of the USSR and Soviet prisoners of war is generally not very well studied in modern Germany.

In Germany, the siege of Leningrad, which was generally one of the most terrible genocidal acts during the entire period of the war of extermination, has been little studied; there are almost no studies on the captured Red Army soldiers whom the Wehrmacht soldiers starved to death in the winter of 1941–42.

There are no central monuments or memorials to these victims in Germany. In the center of Berlin there is a memorial to murdered Jews, in the capital there is a memorial to repressed homosexuals, there are monuments to murdered Roma.

The anti-Russian, anti-Russian genocidal policy of the Third Reich is almost not highlighted in modern Germany. Therefore, of course, Germany needs to finish the work on the mistakes and thoroughly study this complex of war crimes, at least on the basis of existing German archives and documents.

As for the Nuremberg Trials themselves;

One of the reasons why the Wehrmacht was not held accountable during the tribunal and was not recognized as a criminal organization is the distorted, incorrect ideas about “chivalry” on the part of the Allied military.

When the military talks to each other after the capitulation, despite all the crimes committed during the war, they retain ideas about gentlemanly and knightly honor.

They shook hands with the defeated opponents and justified it by saying that the crimes were not committed by officers, that it was only an excess of the perpetrator, the excesses of maddened fighters.

I believe that in the case of Nuremberg, all these officer ideas about the code of honor turned out to be more convincing at the trial than any evidence and irrefutable proof of crimes.

The generals were forgiven their sins contrary to common sense. This may sound like nonsense, considering that [Wehrmacht commanders, Generals] Keitel and Jodl were sentenced to death by hanging, and [Kriegsmarine commanders, Admirals] Raeder and Dönitz were given huge sentences, but, whatever one may say, the regular army as a whole miraculously got away with it. And the reason is that the trial took the form of a military tribunal, that is, people in uniform tried other people in uniform.

Some Wehrmacht servicemen were punished under Soviet jurisdiction. The very first trial for war crimes took place in 1944 in Kharkov; Wehrmacht officers were sentenced to death and executed there. In the end, until 1955, captured Wehrmacht soldiers were held in incredibly harsh conditions in Soviet camps.

But at the Nuremberg Trials, for some reason, the Soviet side decided not to present carefully selected arguments or the results of the investigation of Wehrmacht crimes in the USSR.

This is a complete failure of the Soviet investigation strategy. They could have declared themselves loudly and once again drew attention to the gap between East and West.

This conflict is always present in historical science: Western historians are too fixated on themselves, and little attention is paid to crimes in Eastern Europe.

Perhaps the Nuremberg Trials are the very point in history when the situation could have been changed. And the responsibility for hushing up these crimes during the trial also lies with the Soviet side, they had every chance to tell the world community about the atrocities of the Wehrmacht then.

Unfortunately, we do not know their motivation. This issue could be seriously clarified in a separate study, but for this, Russia must open the KGB archives.

For now, I can only assume that due to the lack of sufficient strategic thinking and competence, the Soviet prosecutors lost here to the Americans, who largely controlled the Nuremberg Trials and achieved their goals through them.

– Considering all of the above and the impasse in which international law has found itself today, to what extent do the results of the Nuremberg Trials still determine our world, how universal are they?

– Both the verdict itself and the results of the investigation, of course, have their weaknesses and shortcomings, but this is the limit that could be achieved in the realities of the 20th century.

The entire previous history of mankind left the Allies no instruments, and they literally invented them, laid the legal foundations for international criminal law. Their brainchild certainly has its inherent flaws, but it functions.

If someone today tries to instrumentalize the Nuremberg Trials in order to legitimize the unleashing of an aggressive war, then, obviously, this person is unfamiliar with both the text of the indictment and the text of the verdict, and his position is unsubstantiated and has nothing to do with history.