Being a person of colour in Russia requires that you live with caution every time you walk in the neighbourhood, nightclub and the streets.

“As we’re not in our country, all we can do is just to be careful,” says Diana Akue a Gabonese doctoral economics student in the city of Yekaterinburg.

Akue as a black woman has been living in Russia for the past nine years and faced her share of discrimination — from being called racial slurs to being barred from certain nightlife hangouts.

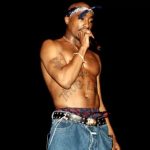

Recently her friend François Ndjelassili (pictured above), was stabbed to death on August 18.

He had also moved from Gabon to study economics at Ural Federal University in Yekaterinburg.

On the fateful day, two men approached Ndjelassili inside a Burger King, harassed and called him racial slurs, then stabbed him with a knife.

In another, more detailed account — one which Akue told a local newspaper appeared to align more closely with reality, based on videos of the incident she said she had seen — events unfolded after Ndjelassili began flirting with a young woman who was accompanied by three Russian men.

The men confronted Ndjelassili and an argument quickly broke out, which then spiraled into a fight outside the restaurant between him and two of the men.

The third Russian man, who was not initially involved in the fight, then came up to Ndjelassili and stabbed him under his arm.

Disparities in these accounts might have appeared more significant were it not for the revelation that the man who killed Ndjelassili — later identified by authorities as Daniil Fomin — may have connections to a white supremacist group.

According to a Russian anti-fascist organization, a closed neo-Nazi channel on the Telegram messaging app with just under 4,000 subscribers announced a fundraiser to help Fomin pay for his legal expenses following his arrest.

“Our Ural colleague Danya Fomin has run into trouble … A lawyer needs to be found as quickly as possible, but Daniil’s family doesn’t have the money. Therefore, I consider it our duty to help him collect the needed amount,” the channel wrote.

Fomin’s parents denied their son had any connections to the group and said they were unaware of the fundraiser, adding that they were paying his legal fees themselves. But this has not assuaged concerns about the possible racial motives behind Ndjelassili’s murder.

“If it’s true the killer was really from that white supremacist group, then who knows what could happen after the court ruling? These guys could get very upset about it,” Akue said.

One of Ndjelassili’s friends told France 24 that he had received death threats after speaking out about the murder. When he contacted the Ural Federal University administration to discuss the incident, he was told to “not talk to anyone” about what had happened.

The university where Ndjelassili was enrolled in a Ph.D. program said in a statement that he had “died tragically.” But it did not mention the circumstances surrounding his death, noting only that he had a “deep respect for Russian culture.”

According to Russia’s Science and Higher Education Ministry, more than 34,000 students from African countries are currently enrolled at Russian universities, an increase of over 4,000 from last year.

President Vladimir Putin highlighted the enrollment uptick in an essay published just before the Russia-Africa Summit in August, as he sought to play up Moscow’s role as an ally to a Global South that he claims has been strongarmed by Western powers.

Similarly, on the eve of the BRICS summit in South Africa last month, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov slammed the “colonial and racist manners” of “Western elites,” who exploit resource-rich countries to pursue goals that “do not reflect the aspirations of all mankind.” Russia, in contrast, stands for “strengthening” and “supporting” Africa, he wrote.

This image of Moscow as a friend of Africa clashes with the persistent issue of racism inside Russia, where pervasive everyday discrimination is often punctuated by extreme acts of violence such as Ndjelassili’s murder.

In the most recent 2020 poll released by the independent Levada Center pollster, 28% of Russians did not believe Africans should be allowed into the country, down from 30% in the year before. Just 4% of respondents said they were ready to be friends or work colleagues with Africans.

“No one talks about racism toward black people in Russia unless someone is killed … which is really frightening now that [Russia] wants to be friends with Africa,” said Anna-Maria Tesfaye, co-founder of Queer Svit, an NGO that helps LGBT people and ethnic minorities from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia affected by the war.

Tesfaye, who is herself black, said her own relatives have faced threats and violence since they immigrated to Russia from Ethiopia in the early 1980s, when the Soviet government drew on anti-colonial rhetoric just as the Kremlin is increasingly doing today.

Yet racism in Russia is often more subtle than explosive in nature. Online apartment rental ads are frequently written “for Slavs only” and it’s not uncommon for people to request a “Slavic” driver when ordering taxis, as people from the Caucasus and Central Asia are widely employed in the sector.

“But people of color also face this kind of casual racism, when people stare at them strangely on the street — they’re watched in the metro and the police are more likely to stop them,” said Natalia Yudina, an analyst at the Moscow-based SOVA Center NGO that monitors nationalism and racism in Russia.

There is no concrete data on the number of black people living in Russia, says Yudina, but some estimates place the number at no more than 60,000 — a small figure compared to the country’s overall population of 143 million.

According to her, 13 racially motivated attacks against black people living in Russia were recorded between 2015 and 2020. But Yudina and activist Tesfaye said they are certain that such attacks in Russia are vastly underreported.

“They haven’t developed ways for protecting themselves collectively as a group, and so most racially motivated attacks against people of color throughout Russia go unnoticed,” Yudina told journalists.

The few cases that do receive media coverage often end in tragedy.

In 2017, a student from Chad was stabbed to death outside university dormitories in Kazan by a group of neo-Nazis. All four assailants were given hefty prison sentences following a jury’s decision.

Years earlier, a student from Ghana was killed while walking on a street in St. Petersburg by a group of white supremacists who were involved in a series of other murders, including a student from Senegal and one from Vietnam.

Of course, many confrontations do not escalate into murder or violence.

Silas Nsangwie, a Nigerian who used to study at a university in the southern city of Saratov, told media of an instance when he was harassed by a man at the supermarket during his first days in Russia in 2015.

“This guy just walked up to me and started shouting at me and calling me ‘monkey.’ He said that I should go back to my country,” Nsangwie recalled.

“It was very vulgar — like, it was really abusive. He was threatening to hit me, but he didn’t.”

Nsangwie, who left Russia in 2020 to continue his studies back home in Nigeria, said it was not uncommon for him to receive racial slurs or strange looks on the bus during his student years.

He decided to leave Russia after one of his instructors in Saratov refused to let him pass a course that would have allowed him to graduate. He believed her reason was the color of his skin.

“I was warned by other students to not enroll in that program. I was told that that instructor in particular is racist and a problem for black students,” Nsangwie said.

“The only thing I could do was just work hard to pass her exams, but that still didn’t help … the dean tried to influence the situation, but she didn’t listen. And that was it.”

Meanwhile, Clement Konadu, who is from Ghana and studies international relations in southern Russia, told reporters that he has yet to face overt discrimination in the country.

“School kids do, you know, turn to look at you, and just point fingers at you,” he said. “But that’s all. Nothing serious.”

Konadu described his relations with Russians as “very good” and mentioned opportunities he’s had to appear on local television to talk about his culture and experiences as a Ghanan living in Russia.

“It depends on how you carry yourself and your demeanor,” he said. “Because … if you carry a charismatic look — it will be very hard for [Russians] to look down on you.”

The other two African students who spoke to journalists shared a similar view, placing a degree of responsibility on the individuals facing discrimination to behave themselves in a manner deemed “appropriate.”

“We’ve been very careful — and just now, maybe, François didn’t really use his wisdom as much as he could have,” said Ndjelassili’s friend Akue.

Activist Tesfaye said she was not surprised that some Africans studying in Russia might hold such views, given that they, as both foreign students and non-whites, often find themselves in an especially vulnerable position — and cope with discrimination in what ways they can.

“It makes me a little bit angry that they are forced to feel this way — to blame themselves if they face racism,” she said.

“Everyone understands that you can face racism regardless of how you behave. And I’m sure François behaved himself, but he was still killed.”

adapted from The Moscowtimes