Every few years, Rwanda’s number-crunchers do something that quietly changes the way we see the whole economy: they rebase the national accounts.

Think of it like updating the map of a fast-growing city. Streets have been paved, new neighbourhoods have sprung up, and old landmarks look different. If you keep using the old map, you will eventually get lost.

This year, when the experts finally unveiled the new map of our economy, the surprise was a pleasant one. The country is about 6% bigger than we thought.

The National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, NISR, has just completed the rebasing of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), updating the reference year from 2017 to 2024 to better reflect changes in the economy.

Rebasing, an exercise normally carried out every three years, had been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic—making this Rwanda’s first update in seven years. Officials explained that rebasing captures structural changes in the economy: new industries, shifts in agriculture, tourism developments, and changes in construction and land values.

This exercise ensures that our GDP figures provide a more accurate picture of the economy’s current structure and value.

The rebased figures show that Rwanda’s GDP for 2024 rose to Rwf 19,918 billion, a 6% increase from the previously published Rwf 18,785 billion. However, this revision also adjusted the growth rate for 2024 downward from 8.9% to 7.2%.

For the second quarter of 2025, GDP at current market prices was estimated at Rwf 5,798 billion, marking a 7.8% increase compared to 6.5% in the first quarter. Services contributed the largest share of GDP at 50%, followed by agriculture at 23% and industry at 21%.

Agriculture grew by 8%, boosted by a 10% rise in food crop production and a 42% surge in export crops, driven largely by improved coffee yields. Tea production, however, dropped by 9%. Farmers in Ruhango and Nyamasheke could feel the difference: sacks of beans and coffee cherries bringing better returns at the market, though tea growers faced tighter margins.

Industry grew by 7%, led by a 12% increase in mining and quarrying, an 8% rise in manufacturing, and a 5% expansion in construction. In Kigali, construction workers are busier than ever building new houses and shops, while factory owners in Bugesera enjoy higher production and orders.

Services posted 9% growth, with wholesale and retail trade up 12%, financial services up 8%, restaurants and transport up 5%, and information and communication recording an 11% jump. Kigali’s internet cafes, mobile money agents, and courier services are bustling, showing how the digital economy is touching daily life.

All figures are based on the new reference year of 2024, which NISR says aligns with international best practices recommending GDP rebasing every five to ten years.

Yusufu Murangwa, the Minister of Finance, admitted that this rebasing was long overdue. “Ideally, you’re supposed to revise the methodologies after three years,” he explained.

“But because of different challenges, in this case specifically, it was because of COVID-19… instead of three years, we are revising after six, seven years.” Like a farmer who delays sharpening his hoe because of a long rainy season, the statisticians had to wait out the pandemic. When they finally sharpened their tools, they found the harvest was a little richer than expected.

An upward revision does not mean the economy suddenly grew overnight. It means that after carefully re-measuring—using fresher data and modern methods—our real economic size turned out to be 6% larger than previously recorded.

An upward revision does not mean the economy suddenly grew overnight. It means that after carefully re-measuring—using fresher data and modern methods—our real economic size turned out to be 6% larger than previously recorded.

Murangwa put it plainly: “It’s not like every year we miss the economy by 6%, no. It means that by the first year, maybe we deviate around, on average, less than 1%.”

Over seven years, Rwanda’s statisticians were about 99% accurate each year. That is like a tailor cutting cloth almost perfectly, then discovering after seven years that the suit is just a touch roomier than the tape measure first suggested.

Why does this matter to ordinary citizens?

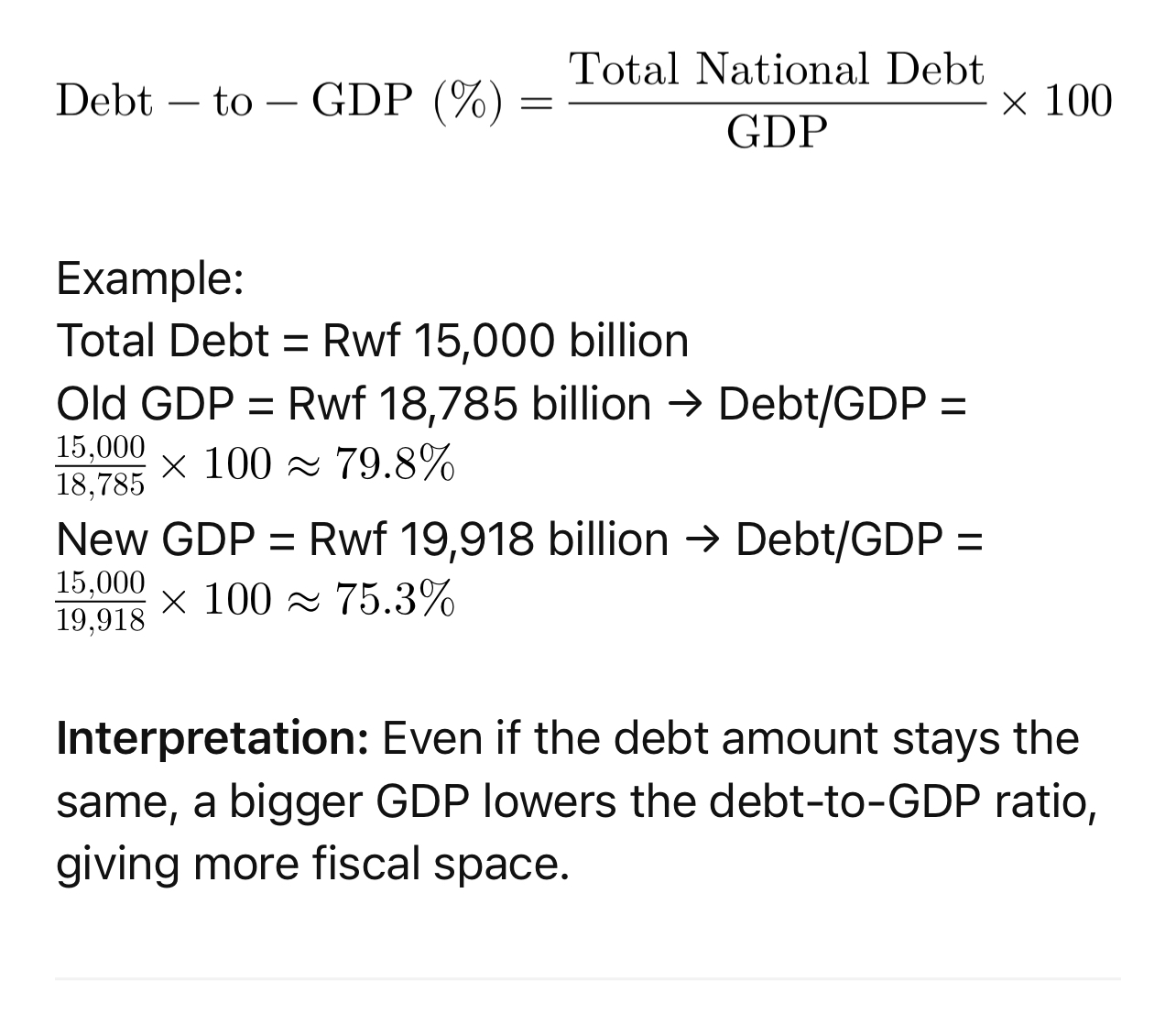

Because the size of our economy is the measuring stick for important ratios—especially debt to GDP, the figure that shows how big our national debt is compared to the economy that must pay it back.

“If you had a debt to GDP ratio of 80%,” Murangwa noted, “maybe now it will be 73%, 78%.” Fewer Rwf of debt for every hundred Rwf of economy is like discovering that your household debt is a bit smaller once you count all your side hustles.

It does not cancel the debt, but it gives a little breathing room.

Ivan Murenzi, the Director General of NISR, drew attention to how the rebasing reveals subtle changes in the economy’s shape. “With agriculture, we do see that the intermediate inputs into agriculture, the costs have gone high… the share of GDP has changed from the last value of 23%… to now 21%.”

That is a quiet but telling shift. Agriculture remains central to Rwanda’s life and culture, but other sectors—especially communications and digital services—are growing faster.

“In communication, we see the share of communication GDP has gone higher,” Murenzi said. It is a sign of the country’s accelerating digital transformation: more people on smartphones, more businesses online, more data flowing across our networks.

He also pointed out something every landlord and tenant can feel: “At household level, we see that the value of rent has gone high.” Anyone who has looked for a place to stay in Kigali, Musanze, or Huye knows that story well.

Murangwa reflected on why it is better to be cautious in measuring the economy. “In managing and measuring the economy, you’d rather be conservative than be very optimistic.

If you are conservative and the results come that you are better than what you are measuring, that is good news.”

It is like a farmer who counts on a modest harvest and ends up with a bumper crop—you plan carefully, and any surprise is a pleasant one.

Yet there is a side of the story that ordinary citizens feel in their pockets. A bigger GDP does not automatically mean everyone’s personal income rises at the same pace.

Economic growth can be like a river that flows wider but not evenly across the valley. Some parts are lush; others remain dry.

When new sectors such as technology, finance, and mining expand quickly, their benefits often concentrate among a smaller group of entrepreneurs and investors.

That is why we have seen a surge in millionaires in Kigali’s leafy suburbs, while rural farmers in Gicumbi or Nyamasheke may still measure progress in sacks of beans or coffee cherries rather than in bank accounts.

This imbalance does not mean the poor are getting poorer; it can mean both rich and poor are growing, but at different speeds.

Like two runners on the same track, both can increase their pace, but if one is sprinting while the other jogs, the gap between them widens.

The volume of the economy grows, but the distribution of that volume—what economists call inequality—can stretch.

Everyday examples make this clear. A taxi driver in Kigali may see fuel prices rise, which offsets the extra income from busier rides.

A mason in Musanze finds more construction jobs thanks to the 5% expansion in building, but wages for helpers rise slowly, leaving the gap between skilled and unskilled workers wide.

A small coffee farmer in Nyamasheke benefits from the 42% increase in export crops, yet local traders capture most of the profits.

Meanwhile, a fintech entrepreneur in Kigali sees his margins double, translating directly into higher revenues and personal income.

Even in hospitality, a restaurant owner may enjoy 5% higher revenues, but the waitstaff sees only small tip increases.

The rebasing is more than just a new number in a spreadsheet. It is a refreshed picture of how Rwanda is changing. Agriculture is still vital but no longer the same share of the economy.

Digital services and communications are gaining weight. Rising rents show the pressures of urban growth.

For leaders and citizens alike, these findings sharpen the questions we ask: How do we support farmers while embracing the digital economy? How do we make housing affordable as cities expand? How do we use a slightly larger fiscal space without falling into complacency?

Murenzi summed it up: “Overall, it enhances or refreshes perspectives… different leaders across sectors can engage better and refine whatever interventions that are to evolve thereafter.”

Rwanda’s economy did not magically grow by 6% overnight. Instead, we simply measured it more carefully and discovered it was already larger than we thought. It is like pulling back a curtain and seeing the landscape in brighter daylight.

For ordinary Rwandans, the message is simple: the country is on a surer footing than the old numbers suggested.

But just as a farmer who finds his granary a little fuller must still plan for next season, the nation must use this updated map wisely—investing in new sectors, supporting those left behind, and keeping its debt under watch.

Sometimes, good news is not a sudden windfall but the quiet satisfaction of knowing you have been doing things right all along, even as you keep working to ensure that the benefits of growth reach everyone, from the new millionaire in Kigali to the bean grower in the hills.