Rwanda’s nightlife restrictions have spiraled into an economic and social crisis, reshaping lives in ways few anticipated. On August 1, 2023, President Paul Kagame chaired a Cabinet meeting at Urugwiro Village that approved new regulations limiting non-essential services to 1 a.m. on weekdays and 2 a.m. on weekends. The rules, effective September 1, 2023, were presented as a way to regulate noise pollution and safeguard public order. Exceptions could only be granted through the Rwanda Development Board.

But what was introduced as a simple regulation has turned into a policy with devastating economic consequences. Taarifa has conducted a thorough investigation and surveys, visited affected businesses, and intimately discussed with business owners for the past two years. We also had very detailed questionnaires filled and data collected. The results paint a grim picture.

Enforcement fell largely to police and local authorities. With no clear legal instruments, penalties were applied arbitrarily. Businesses saw sound systems confiscated, venues shut down, and fines ranging from Rwf300,000 to Rwf3,000,000 imposed—often without official receipts. In practice, the system became a cash cow for some officers, with bribes demanded to overlook violations or allow bars to stay open a few minutes longer.

Local defense units (Irondo) enforced the policy with batons. They stormed venues, unplugged sound systems, and ordered patrons to leave. Customers fled without paying, leaving owners with mounting losses.

Some venues tried locking clients inside, but police raids sometimes ended in chaos and arrests. Nightclubs that once made Rwf75 million a night now barely scrape Rwf25,000. “Sometimes I would find US$20,00 or US$30,00 cash in the safe, and I knew this was from tourists. Now we don’t even find US$500,” said a nightclub manager in Kigali. “It’s devastating.”

In Rubavu, a venue that used to earn Rwf50,000,000 nightly now manages only Rwf10,000,000. “Just when we are starting to make money, it’s time to close,” says a club owner in Rubavu, whose DJ was laid off and is now in Kigali trekking bar to bar looking for a job to take care of his family in a painful situation.

One Kigali club owner, unable to pay staff or suppliers, is now battling nine lawsuits. He was running a booming business in Kimihurura. He started with Rwf70 million, barely before he broke even, the policy hit him. He closed and went on to find a job with a brewery. “I am lucky I found a job, but all my staff are unemployed. Sometimes they call me asking for Rwf5,000 to buy food.”

One Mutesi was once running a booming lounge. She was making a kill, employing about 50 staff and hiring additional workers on weekends. Her books were hitting Rwf700 million annually. But after the restrictions, she was forced to shut down. Having acquired a loan at I&M Bank, she now fears defaulting. To stay afloat, she switched to running a small liquor store and juggling side hustles, just to keep up with loan payments. Her story, once of growth and success, is now one of survival.

The ripple effects extend through the entire value chain. Farmers in Nyabihu have dumped unsold produce—carrots, cabbages, tomatoes—while suppliers of basics like soap, sugar, milk, onions, chili, and charcoal see plummeting demand. Transporters and taxi-moto riders also report steep losses. Jean Claude, a taxi driver, once operated on a shared schedule: his partner worked days, he drove nights. Today, he barely makes enough to pay rent or feed his family. “It’s embarrassing to call my father in the village to send me beans and potatoes to feed myself. We don’t deserve this,” he says.

Workers have borne the brunt. Many venues laid off up to 90 percent of staff. Students who once paid tuition by working as waitresses and bartenders have dropped out. More than 50 young women told Taarifa they turned to prostitution in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, and the UAE after losing jobs. “I am not a trader or a consultant. I dropped out of school. What else do you think takes me to Lagos? How do you think I afford the ticket? Don’t ask me useless questions. I am a sex worker. That’s it,” a 23 year old girl who was working as an accountant says. She has not been working for a year now, but she found a new job, a demeaning one.

Fathers too lost their livelihoods and can no longer feed their families. Alice Mutesi, a waitress, lost her job while pregnant and later suffered a miscarriage from stress. In Nyamirambo, a mother says her daughter slid into drug use and ended up in prison after losing her restaurant job.

Cleaners also lost work. So did DJs, musicians, photographers, and event organizers. Many have abandoned their professions altogether.

Jean Marie Nahimana, a musare (private driver), used to make a living by safely driving drunk clients home. “No more business for us. Nowadays I get one or two clients. There are very few people at night needing me anymore,” he says. Now he roams around bars and restaurants, yawning idly, hoping for a customer that never comes.

For police, the measure did yield one result: fewer drunks and road accidents late at night. But drivers say they had already adopted solutions by hiring private drivers. “This was not the way to kill the business,” one driver remarked.

A popular Issa in Kimihurura who was making earning massively from selling cheesed potatoes is no more. He operated a lucrative business nearby Envy Nightclub. He vanished and is no where to be seen. Even the nightclub is now home to rats and cockroaches. The landlord’s numbers are not adding up.

Event organizers are no where to be seen. No business. “I dare you not. Try and see. Who wants to organise a concert that ends at midnight?,” says Emile, a seasoned event organizer who confessed that all his last 15 years his career was to organise events. “Now I have a small studio trying to see if I can get clients who need content, but it’s a misadventure.”

Hotels and tour operators are also reeling. Visitors who once stayed out to enjoy Rwanda’s nightlife now cut trips short, taking disposable income back home. “Tourists come and go back with their disposable money still in their pockets,” one hotelier complained.

Indeed, alcohol has health effects, but for an objective decision-maker equipped with numbers, there was no scientific or statistical rationale for the decision. The Institute of Statistics admitted in its report yesterday that it had no evidence whether the policy had a positive or negative impact—nothing. In bars and restaurants, inputs are not just alcohol. They include vegetables, meat, tissue, toilet paper, soap, milk, sugar, honey, sound systems, water, onions, tomatoes, chili, and much more. But by trivializing alcohol, policymakers ignored the entire value chain and delivered a devastating blow to the economy.

The losses are more than financial—they’re existential. For some, a franc is not just a franc. A low-income household can stretch Rwf20,000 into rent, school fees for a term, and still afford soap and toothpaste. For an elite family, that same Rwf20,000 is just fuel for a guzzler from Kagugu to downtown. Two different worlds. Rwanda is not an industrial economy. It does not provide tangible jobs for the majority. It is an infant economy where many live paycheck to paycheck. A roasted potato vendor smiles home with a kilo of rice at the end of the night. Policymakers, critics say, overlooked this fragile ecosystem and imposed a misguided policy.

Tourism has also taken a beating. During a Basketball Africa League event, fans were forced to leave early because of the curfew. Organizers later concluded Rwanda was no longer an ideal host for international events. The restrictions contradict the government’s own multimillion-dollar “Visit Rwanda” campaign, which promotes the country as a lifestyle and leisure destination.

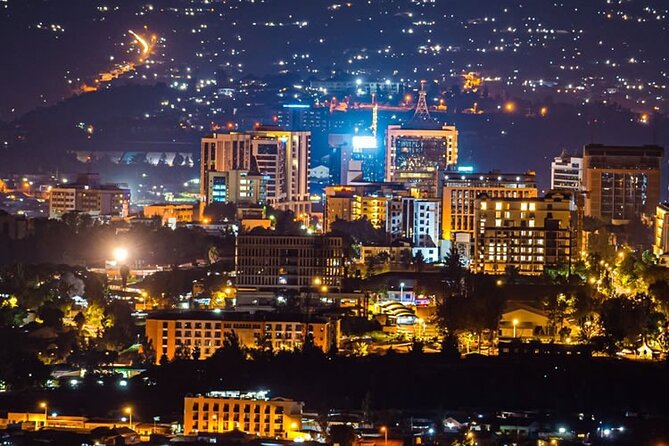

At night. 3:0am the whole country is silent. Only ghosts walk in the streets of Kigali. In Musanze, not even a human being walks the streets. In Rwamagana, Rubavu and other towns, nothing can be hard out. Dead silent.

But here is a twisted reality. Alcohol sales themselves have not declined. Bralirwa and other beverage companies report steady demand. Bralirwa posted a profit of Rwf 18.4 billion in the first half of 2025. Revenue rose to Rwf 32 billion, up from Rwf 26 billion in the same period of 2024.

The Ministry of Health and Rwanda Biomedical Centre had argued the rules would curb youth drinking. That has not happened, at least from the numbers. The question is, was the policy about drinking alcohol or something else?

The parliament never was engaged. Members of parliament read the cabinet communique like every ordinary citizen. They have no idea where it came from. And they have never ask a question. End of business. Go figure.

To set the record straight, Trade Minister Prudence Sebahizi and Finance Minister Yusuf Murangwa clarified in a press conference yesterday that there was never a government decision to “halt nightlife.”

Instead, they said, it was about considering citizens’ welfare. But now, they acknowledged, the policy is being revisited. “As a government, we have agreed to mobilize the private sector to work 24 hours where it is possible. We are working on the modalities,” Sebahizi said. “We will have intergovernmental consultations and we also consult the private sector. Very soon, not later than two weeks, we should be able to publish what has been agreed across the stakeholders.”

From an economic perspective, Sebahizi explained the government’s intent was to promote productivity by enabling businesses to operate 24/7, supported by services and incentives. “So there will be a set of incentives from the government, but also the private sector has to be mobilized to increase their productivity by working more hours than they are used to,” he said. Murangwa added: “We hope these discussions will lead to a good review of whatever policies were taken and see whether we take them forward as they are, or we modify them a little bit, or completely reverse them. These are things that can always be reviewed.”

For many, the answer is simple: change course. “One thing about Rwanda is that it listens and understands the plight of the people,” one businessman said. “It’s time to reverse this policy.”